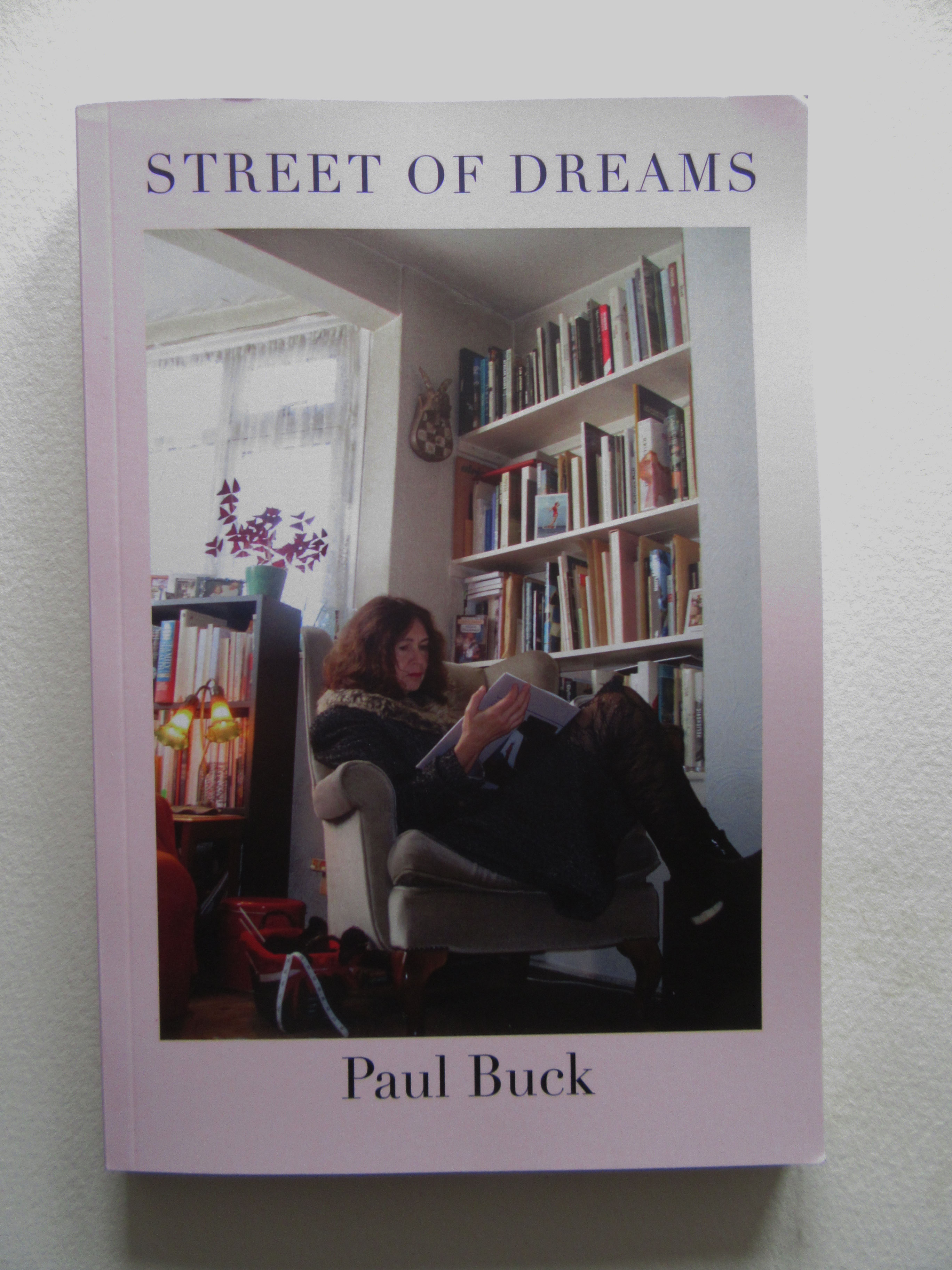

Paul Buck

STREET OF DREAMS

2020

London. Charing Cross Road. I must have walked up and down that road two or three thousand times. Perhaps ten thousand. Who knows? How to calculate a figure with any form of accuracy when it traces back forty years to my early teens? Can’t I make a stab in the dark, perhaps like Simenon when he claimed to have had sex with ten thousand women since the age of thirteen and a half in his ‘need to communicate’?

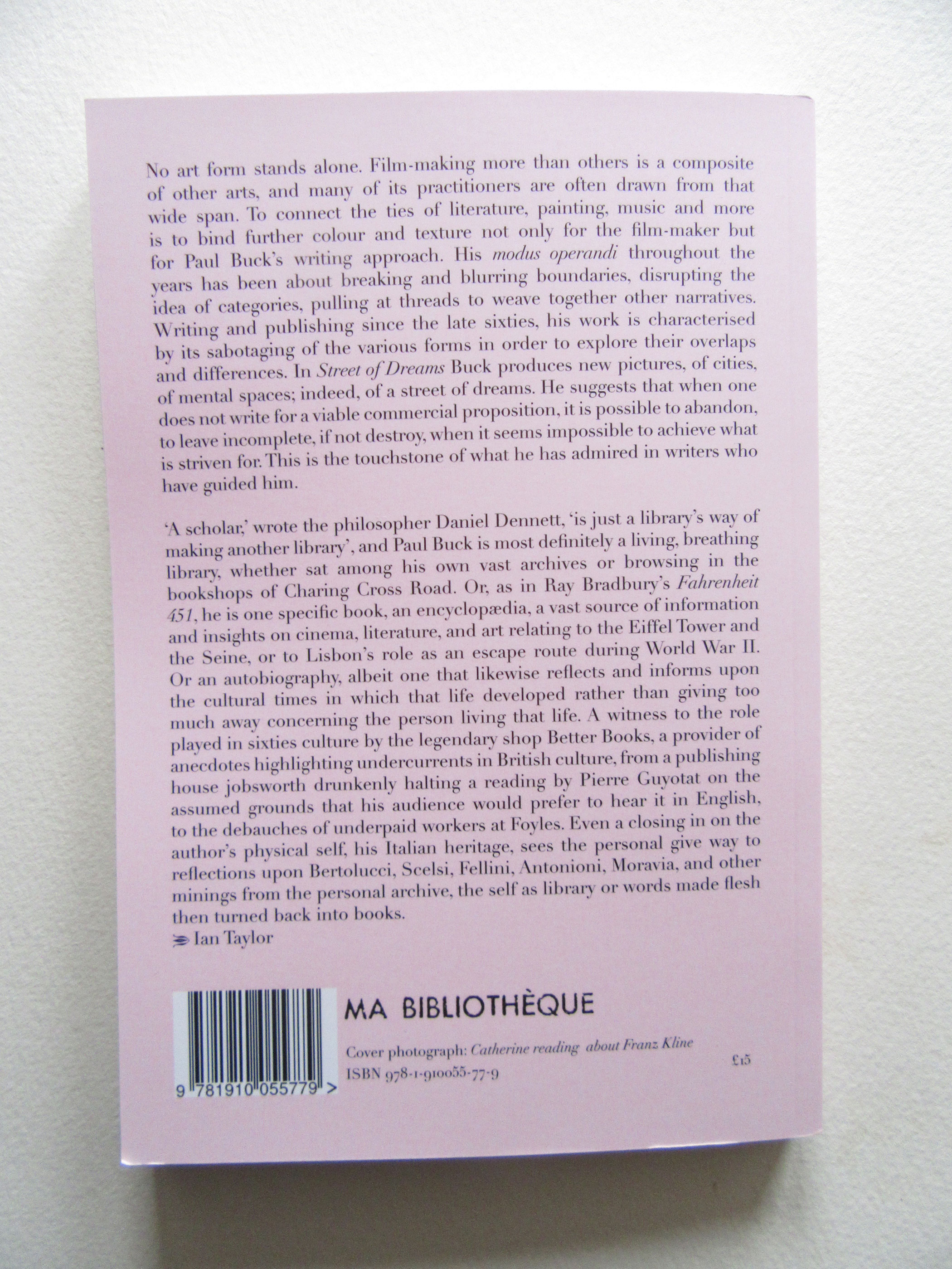

No art form stands alone. Film-making more than others is a composite of other arts, and many of its practitioners are often drawn from that wide span. To connect the ties of literature, painting, music and more is to bind further colour and texture not only for the film-maker but for Paul Buck’s writing approach. His modus operandi throughout the years has been about breaking and blurring boundaries, disrupting the idea of categories, pulling at threads to weave together other narratives. Writing and publishing since the late sixties, his work is characterised by its sabotaging of the various forms in order to explore their overlaps and differences. In Street of Dreams Buck produces new pictures, of cities, of mental spaces; indeed, of a street of dreams. He suggests that when one does not write for a viable commercial proposition, it is possible to abandon, to leave incomplete, if not destroy, when it seems impossible to achieve what is striven for. This is the touchstone of what he has admired in writers who have guided him.

‘A scholar,’ wrote the philosopher Daniel Dennett, ‘is just a library’s way of making another library’, and Paul Buck is most definitely a living, breathing library, whether sat among his own vast archives or browsing in the bookshops of Charing Cross Road. Or, as in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, he is one specific book, an encyclopædia, a vast source of information and insights on cinema, literature, and art relating to the Eiffel Tower and the Seine, or to Lisbon’s role as an escape route during World War II. Or an autobiography, albeit one that likewise reflects and informs upon the cultural times in which that life developed rather than giving too much away concerning the person living that life. A witness to the role played in sixties culture by the legendary shop Better Books, a provider of anecdotes highlighting undercurrents in British culture, from a publishing house jobsworth drunkenly halting a reading by Pierre Guyotat on the assumed grounds that his audience would prefer to hear it in English,

to the debauches of underpaid workers at Foyles. Even a closing in on the author’s physical self, his Italian heritage, sees the personal give way to reflections upon Bertolucci, Scelsi, Fellini, Antonioni, Moravia, and other minings from the personal archive, the self as library or words made flesh then turned back into books.

–> Ian Taylor

No art form stands alone. Film-making more than others is a composite of other arts, and many of its practitioners are often drawn from that wide span. To connect the ties of literature, painting, music and more is to bind further colour and texture not only for the film-maker but for Paul Buck’s writing approach. His modus operandi throughout the years has been about breaking and blurring boundaries, disrupting the idea of categories, pulling at threads to weave together other narratives. Writing and publishing since the late sixties, his work is characterised by its sabotaging of the various forms in order to explore their overlaps and differences. In Street of Dreams Buck produces new pictures, of cities, of mental spaces; indeed, of a street of dreams. He suggests that when one does not write for a viable commercial proposition, it is possible to abandon, to leave incomplete, if not destroy, when it seems impossible to achieve what is striven for. This is the touchstone of what he has admired in writers who have guided him.

‘A scholar,’ wrote the philosopher Daniel Dennett, ‘is just a library’s way of making another library’, and Paul Buck is most definitely a living, breathing library, whether sat among his own vast archives or browsing in the bookshops of Charing Cross Road. Or, as in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, he is one specific book, an encyclopædia, a vast source of information and insights on cinema, literature, and art relating to the Eiffel Tower and the Seine, or to Lisbon’s role as an escape route during World War II. Or an autobiography, albeit one that likewise reflects and informs upon the cultural times in which that life developed rather than giving too much away concerning the person living that life. A witness to the role played in sixties culture by the legendary shop Better Books, a provider of anecdotes highlighting undercurrents in British culture, from a publishing house jobsworth drunkenly halting a reading by Pierre Guyotat on the assumed grounds that his audience would prefer to hear it in English,

to the debauches of underpaid workers at Foyles. Even a closing in on the author’s physical self, his Italian heritage, sees the personal give way to reflections upon Bertolucci, Scelsi, Fellini, Antonioni, Moravia, and other minings from the personal archive, the self as library or words made flesh then turned back into books.

–> Ian Taylor

184 pages

205 mm x 140 mm

Paperback

ISBN 978-1-910055-77-9

£15.00

SPECIAL OFFER:

Buy STREET OF DREAMS with Paul Buck, LIBRARY. A SUITABLE CASE FOR TREATMENT (2018) for £25.00

Next book ->

205 mm x 140 mm

Paperback

ISBN 978-1-910055-77-9

£15.00

SPECIAL OFFER:

Buy STREET OF DREAMS with Paul Buck, LIBRARY. A SUITABLE CASE FOR TREATMENT (2018) for £25.00

Next book ->