Riccardo Boglione

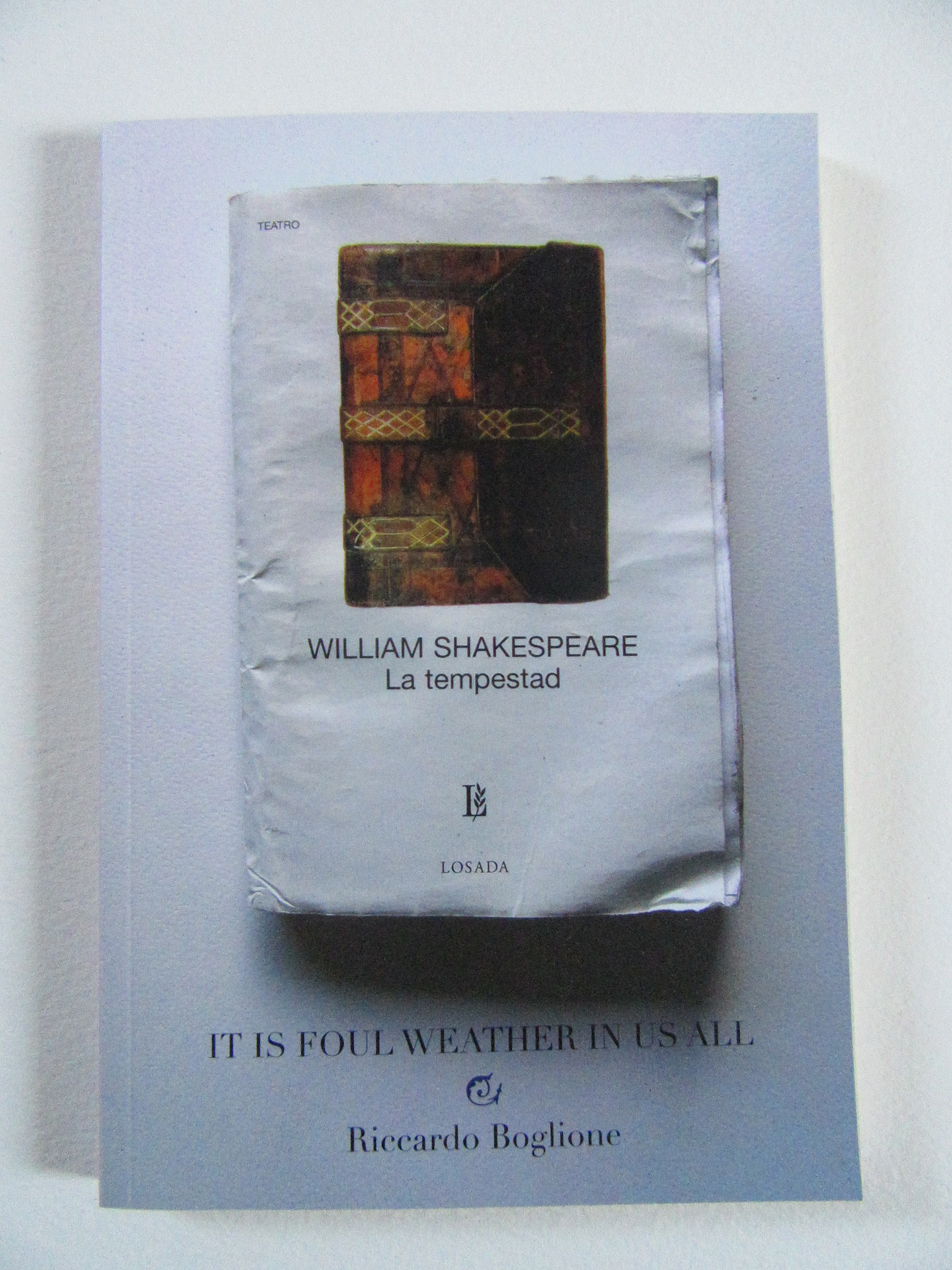

IT IS FOUL WEATHER IN US ALL, 2018

Contributors: Paolo Argeri,

Luz María Bedoya, Carlos Capelán, Claude Closky, Felipe Cussen, Pablo

Echaurren, Belén Gache, Sharon Kivland, Michalis Pichler, Nick Thurston, Pablo

Uribe, Luca Vitone

Riccardo Boglione sent

copies of Shakespeare’s The Tempest to

twelve artists living in Europe and America, each copy in the language of the

country of residence of the artists, asking them to leave the book outside to

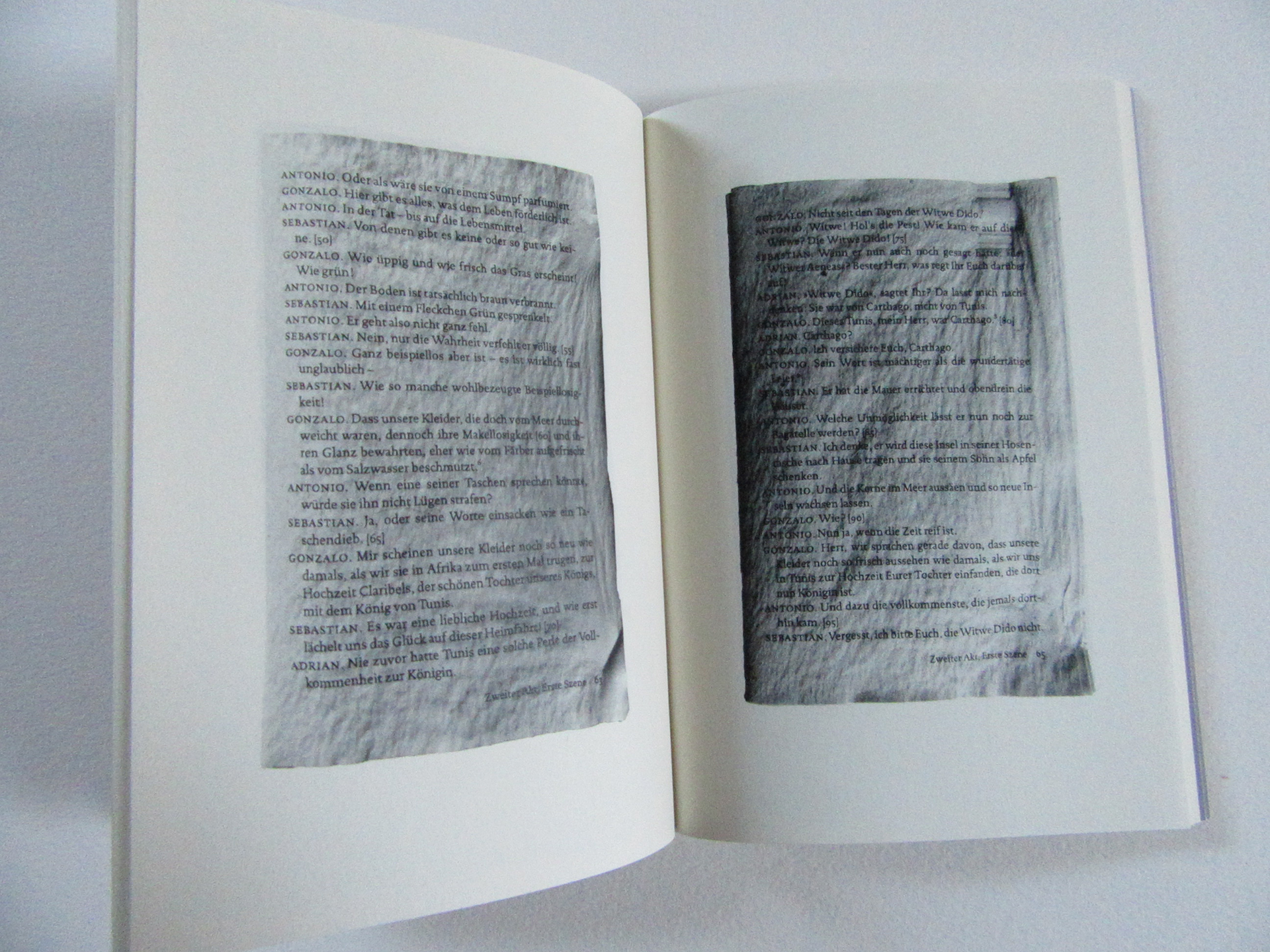

the weather for as long as they wanted. The pages from those mistreated volumes

reconstruct a Frankensteinian version of the play. In an extension of the

metaphor of the tempest, the author gathers a small collection of injured

volumes, mimicking Prospero’s book. Simultaneously he produces a version of

Shakespeare’s play that shakes notions of authority (who is the real author?

The invited artists? The English Bard? Boglione? The translators? Bad weather?

Time?) and aesthetics (the ‘work’ of rain, snow, wind, and sun transformed the

text’s characteristics, giving it a sculptural dimension that obfuscates its

literary one). At stake once again, the perpetual dualisms: objects and words,

nature and culture, Old and New World.

‘In 1919, Marcel Duchamp sent his sister a wedding present from Buenos Aires. He proposed that she leave a book outside, at the mercy of the elements, to be wind-warped and roughly read by its environment. It was referred to as the Readymade Malheureux. Almost a century later, Boglione offers some dozen such gifts anew, but in place of the geometry textbook used by Suzanne Duchamp, the book in question is William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Prospero famously promises to bury his magic staff ‘certaine fadomes in the earth’ and then drown his grimoire ‘deeper then did euer Plummet sound’. Despite his abjurations, however, Prospero continues to command and enthrall with his charms. Here too, the gorgeous resiliency of text perpetuates enchantments with new spellings and ‘seuerall strange shapes’. Behold the rough magic that remains.’

-> Craig Dworkin

‘The monuments of Classical Literature: adored, dead. Traditionally, we bring them back to life by engaging with their time-tested ideas: ideas that have been manufactured and handed down by institutions of learning. A pin-hole view that can also be necrophilic. It Is Foul Weather In Us All contests this relationship to received ideas, inviting artists and writers to use Shakespeare—literally. By instructing the participants to leave their copies ofThe Tempest out in the rain, Boglione constructs a transformative reader-writer dialogue that is truly present—what can be more present than our daily weather?’

- >Robert Fitterman

‘As if by a miracle, Boglione’s sacrilegious instigation to book ruination proves to be a profession of love to book culture and literature. He turns out to be a sorcerer capable of converting destruction into production, whose mastery is on a par with Prospero’s magical power. Prospero’s words could be Boglione’s own calming words addressed to the very likely alarmed reader: ‘Be collected. / […] tell your piteous heart / There’s no harm done.’

->Annette Gilbert

Riccardo Boglione (1970) was born in Genoa, Italy. He received his Ph.D. in Romance Languages from the University of Pennsylvania with a dissertation on Radical Texts in the Italian New Avant-garde. He now lives in Montevideo, Uruguay, where he writes about art for a newspaper and several magazines. His main interests are avant-garde movements and conceptual literature. He is the founder of Crux Desperationis (2011-), the first journal devoted to conceptual writing.

From Adam Smyth, BOOKS WITHOUT READERS

‘Just because a book doesn’t have a reader, doesn’t mean things don’t happen to it. To produce It Is Foul Weather In Us All, Riccardo Boglione posted copies of The Tempest to twelve artists in Europe and North America, each in the language of the country where the artist lived, and requested that the book be left outside. Time passed; winds blew and rain fell; and the books warped and turned. The copies were regathered and the resulting, weather-battered pages were combined to produce a hybrid Tempest: a damaged book that was also now durational, a record of time passing, and of the conditions it had endured’.

It Is Foul Weather In Us All is in part about how much happens to a book even when no one is around: how books don’t need readers to transform, and how this is a volume whose author isn’t properly Shakespeare or Boglione, but time, and the elements.

‘In 1919, Marcel Duchamp sent his sister a wedding present from Buenos Aires. He proposed that she leave a book outside, at the mercy of the elements, to be wind-warped and roughly read by its environment. It was referred to as the Readymade Malheureux. Almost a century later, Boglione offers some dozen such gifts anew, but in place of the geometry textbook used by Suzanne Duchamp, the book in question is William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Prospero famously promises to bury his magic staff ‘certaine fadomes in the earth’ and then drown his grimoire ‘deeper then did euer Plummet sound’. Despite his abjurations, however, Prospero continues to command and enthrall with his charms. Here too, the gorgeous resiliency of text perpetuates enchantments with new spellings and ‘seuerall strange shapes’. Behold the rough magic that remains.’

-> Craig Dworkin

‘The monuments of Classical Literature: adored, dead. Traditionally, we bring them back to life by engaging with their time-tested ideas: ideas that have been manufactured and handed down by institutions of learning. A pin-hole view that can also be necrophilic. It Is Foul Weather In Us All contests this relationship to received ideas, inviting artists and writers to use Shakespeare—literally. By instructing the participants to leave their copies ofThe Tempest out in the rain, Boglione constructs a transformative reader-writer dialogue that is truly present—what can be more present than our daily weather?’

- >Robert Fitterman

‘As if by a miracle, Boglione’s sacrilegious instigation to book ruination proves to be a profession of love to book culture and literature. He turns out to be a sorcerer capable of converting destruction into production, whose mastery is on a par with Prospero’s magical power. Prospero’s words could be Boglione’s own calming words addressed to the very likely alarmed reader: ‘Be collected. / […] tell your piteous heart / There’s no harm done.’

->Annette Gilbert

Riccardo Boglione (1970) was born in Genoa, Italy. He received his Ph.D. in Romance Languages from the University of Pennsylvania with a dissertation on Radical Texts in the Italian New Avant-garde. He now lives in Montevideo, Uruguay, where he writes about art for a newspaper and several magazines. His main interests are avant-garde movements and conceptual literature. He is the founder of Crux Desperationis (2011-), the first journal devoted to conceptual writing.

From Adam Smyth, BOOKS WITHOUT READERS

‘Just because a book doesn’t have a reader, doesn’t mean things don’t happen to it. To produce It Is Foul Weather In Us All, Riccardo Boglione posted copies of The Tempest to twelve artists in Europe and North America, each in the language of the country where the artist lived, and requested that the book be left outside. Time passed; winds blew and rain fell; and the books warped and turned. The copies were regathered and the resulting, weather-battered pages were combined to produce a hybrid Tempest: a damaged book that was also now durational, a record of time passing, and of the conditions it had endured’.

It Is Foul Weather In Us All is in part about how much happens to a book even when no one is around: how books don’t need readers to transform, and how this is a volume whose author isn’t properly Shakespeare or Boglione, but time, and the elements.